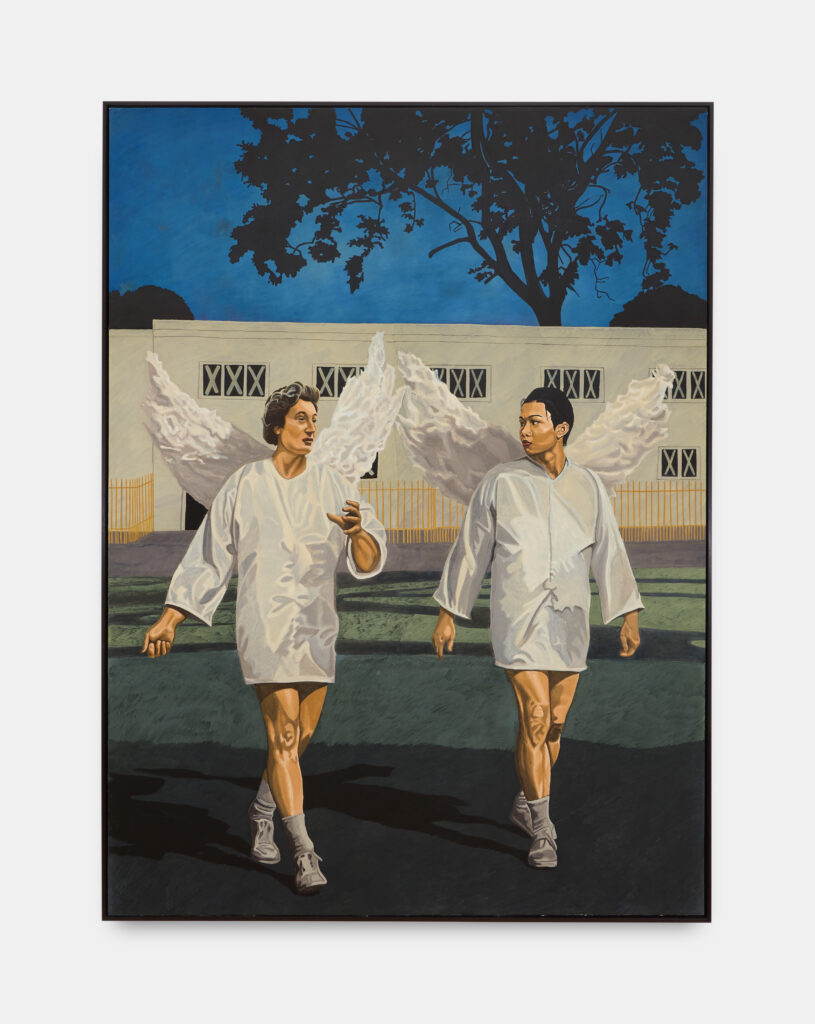

In Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings’ Arcadia, a fresco depicts two androgynous figures, dressed as angels, walking towards the viewer, away from a building with windows marked by white crosses. The building in Angelus Novus is British fascist Oswald Mosley’s Second World War home; the crosses, tape to protect the windows from bomb damage; the angels, taken from an archival image of a pride parade. As in Quinlan and Hastings’ permanent commission for London’s St James’ Park station – which the exhibition at Arcadia Missa expands on – these figures are angels of history, referencing philosopher Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940). In his text, discussing a monoprint by artist Paul Klee, Benjamin outlines a metaphorical theory of history; “his face turned towards the past”, the angel witnesses not progress but a chaotic pile of debris, the accumulation of which we see as history.

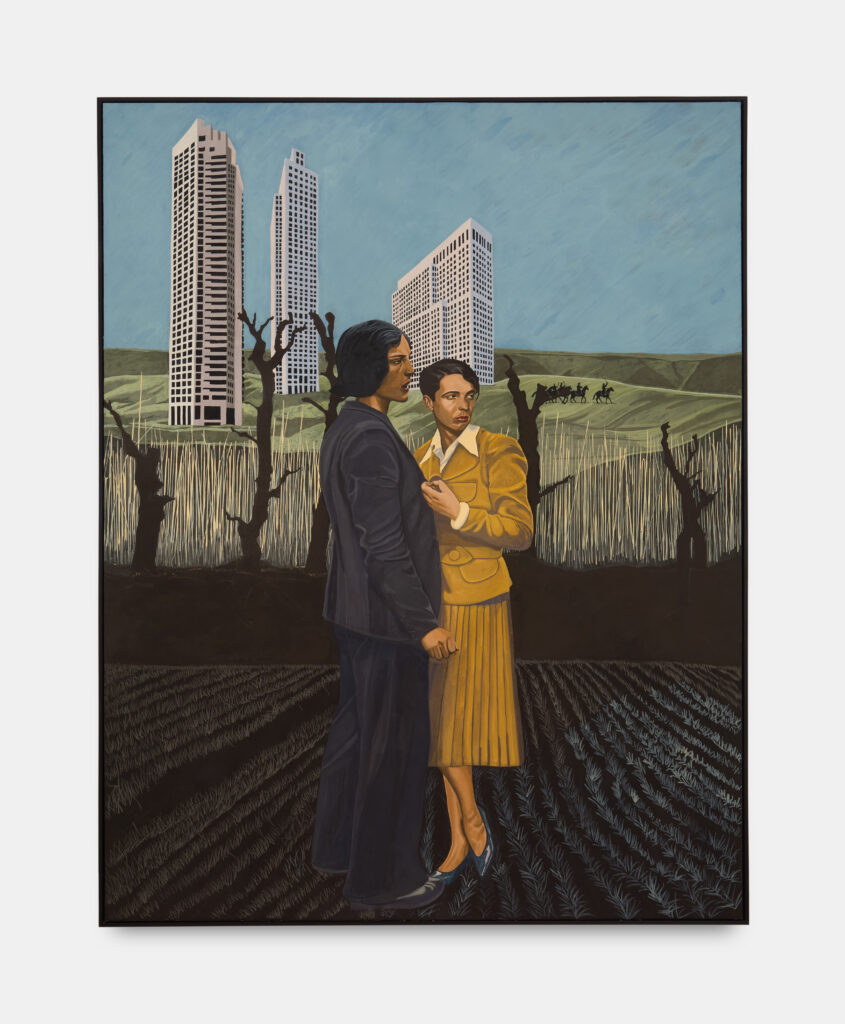

In Quinlan and Hastings’ work, we see the debris of history; figures pulled from queer archives, compositions borrowed from the annals of the art history, architectures drawn from WWII ephemera. In the fresco The Triumph of Death, we see two ambiguously gendered people standing in an uncanny anachronic scene, figures Quinlan and Hastings position in the post-war period of political consensus. From the wreckage of the war, in the UK, came a project of reconstruction and social consensus, in response to what economist William Beveridge described as “Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness”.

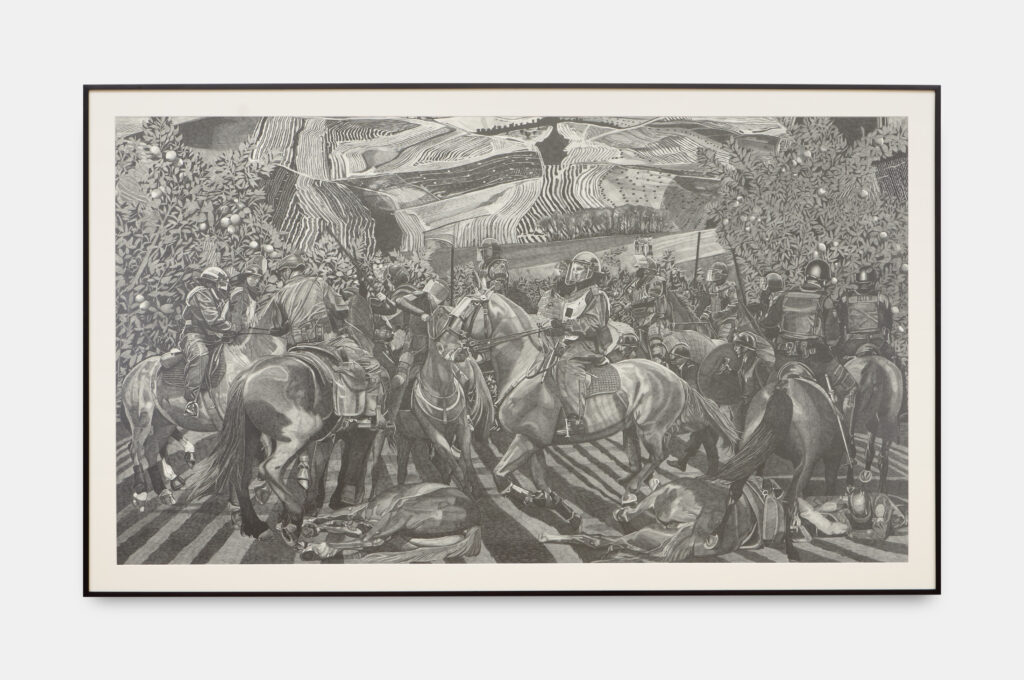

But, as cultural theorist Stuart Hall outlined in his 1988 book, The Hard Road To Renewal, the social consensus – already a traditionalist one of white heteronormativity – was undermined and dismantled under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, as she exploited discontent with the welfare state to promulgate an authoritarian, populist neoliberal ideology. In Arcadia, authoritarianism takes the form of mounted police, evoking scenes from the 1981 Poll Tax riots or the 1984 Battle of Orgreave; in the fresco The Triumph of Death – inspired specifically by an eponymous fresco in Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo – death, in this case riot police, rides through the landscape on horseback; in Roses, the composition informed by Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano, the police engage in battle, not against demonstrators or striking workers, but against themselves.

As in Uccello’s painting, the fields in the background of Quinlan and Hastings’ graphite drawing rise up to meet the foreground; the landscapes in Arcadia are agricultural, cultivated by human ambition. For Quinlan and Hastings, agricultural land holds a double potential in creating images of the future; the landscape exists not only as a potentially utopian space, in line with a history of the commons, but also as a site of primitive accumulation that continues to perpetuate systems of class and compulsory heterosexuality, through specific notions of reproductive futurity. By placing queer and androgynous figures into these landscapes, such images of the future are brought into question. The past, present and future sit in tension in Quinlan and Hastings’ work; pride parades exist alongside the hostilities of WWII; temporally ambiguous skyscrapers penetrate feudal farmland; contemporary riot police populate a renaissance composition. In Spectres of The Atlantic, scholar Ian Baucom (synthesising the thoughts of Walter Benjamin and economist Giovanni Arrighi) writes “Time does not pass, it accumulates…” and this sentiment holds true in Quinlan and Hastings’ work, both in media and in content. Alongside the archive images and compositions that permeate Arcadia, Quinlan and Hastings’ practice enfolds processes drawing from antiquity – fresco, etching, egg tempera, the mosaics of their St James’ Park station commission – to interrogate histories of power, social injustice and the process of history itself.

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings (b. 1991, Newcastle, London) are a London-based artist duo known for their exploration of queer identity, urban spaces, and the politics of sexuality. Recent solo exhibitions include at Arcadia Missa, London; Eden Eden/Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin (2024); Maison Populaire, Montreuil; Kunsthall Stavanger, Stavanger; Huset For Kunst & Design, Holstebro (2023); Tate Modern, London; Kunsthalle Osnabrück (2022); Mostyn, Llandudno; Humber Street Gallery, Hull (2020); and Queer Thoughts, New York (2018). Selected group exhibitions include at Vanderbilt University Museum of Art, Nashville; Yutaka Kikutake Gallery, Tokyo; Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Bruton (2024); Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry (2023); High Art, Arles (2022); Pinchuk Art Centre, Kiev; Circa, London, Seoul, and Tokyo; The Eva Biennial, Limerick (2021); Hayward Gallery, London; Whitechapel Gallery, London (2019); The Cruising Pavilion, Venice 16th Architecture Biennale (2018). Selected performances include ICA, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Southbank Centre, London (2019). Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hasting’s work is in major public collections including British Museum, London; British Council Collection, London; Government Art Collection, London; Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield; The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; The Box, Plymouth; David Roberts Art Foundation, London; Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool; Deutsche Bank Collection, Berlin.

William Beveridge, Social Insurance and Allied Services (Beveridge Report), 1942. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/coll-9-health1/coll-9-health/

Ian Baucom, Spectres of the Atlantic, 2005. p.24