Plinth: 90 × 45 × 35 cm, Book: 26 × 20 × 2 cm

Ruin/Rien links together a cluster of events associated with the French Revolution in the late 18th century and the concept of the autonomous artwork.

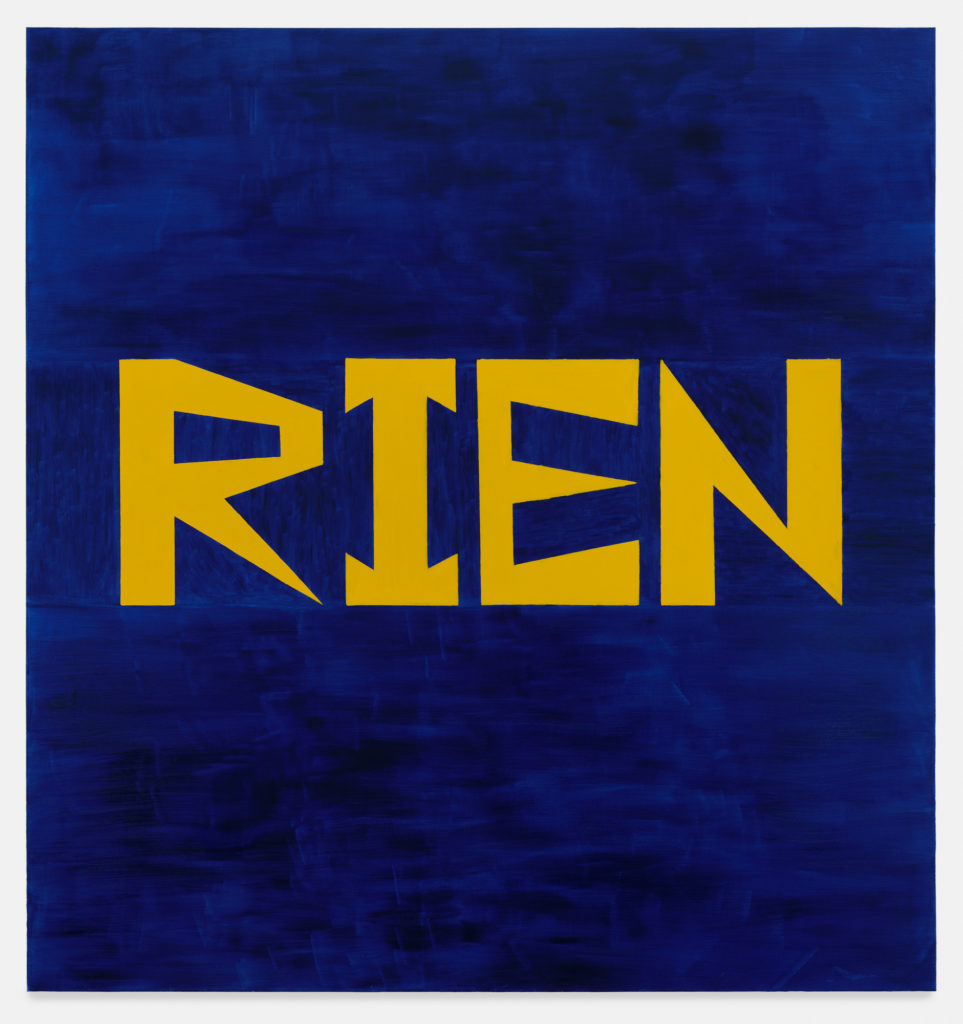

On the day of the storming of the Bastille, King Louis XVI wrote a single word in his diary: “rien” (nothing). This has been interpreted as a sign of the aristocracy’s disconnect from the activities of the proletariat. But it is more likely to have been simply a reference to the day’s hunt, in which the king killed nothing. The word “RIEN” appears here as a six-foot painting based on Ed Ruscha’s famous painting Oof. Ruscha was part of a movement of artists who played at the boundary of two ideas: that art draws its power from a kind of semantic emptiness, and that this emptiness itself characterizes everyday urban life.

During the storming of the Bastille, a protestor found and rescued a manuscript tucked into the walls of a prison cell. This was the work of a recent inhabitant, the Marquis de Sade, who had been moved from the Bastille just 10 days previously. Bastille playfully reconstructs this anecdote in brick and paper, blocking out part of the outside world and evoking both the autonomy of minimalist sculpture and the prison cell.

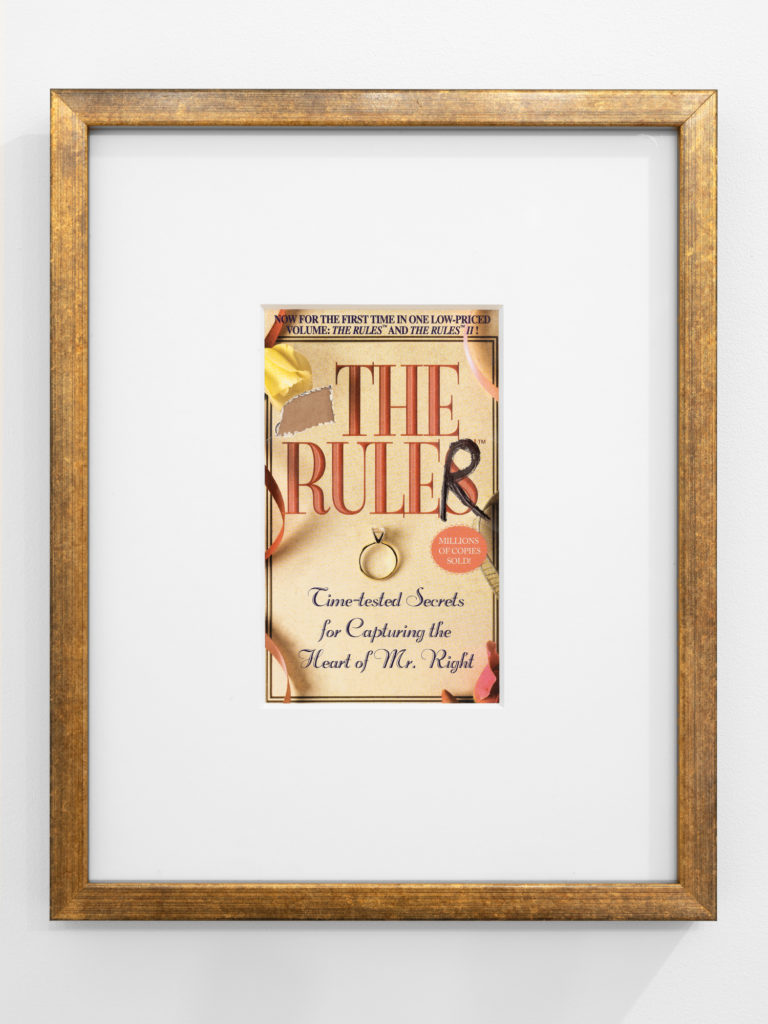

De Sade was a scion of the aristocracy but was sprung from his class position by his perverse sexual desires. A facing work, The Ruler, repurposes the cover of a famous heterosexual dating manual offering “capture”, gesturing to how, just as much as some desires can dislodge us from social norms, others can fuse us more closely to them.

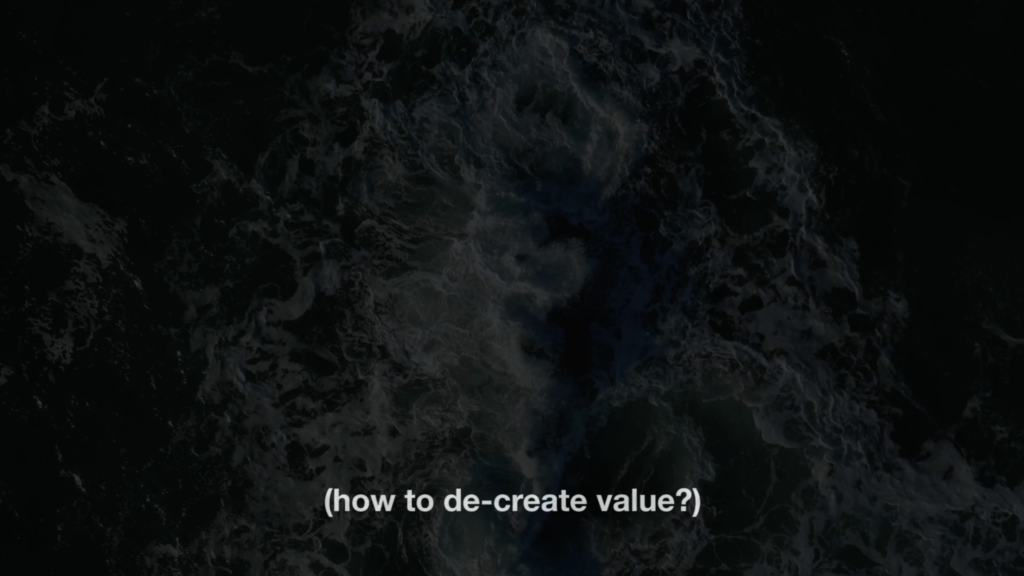

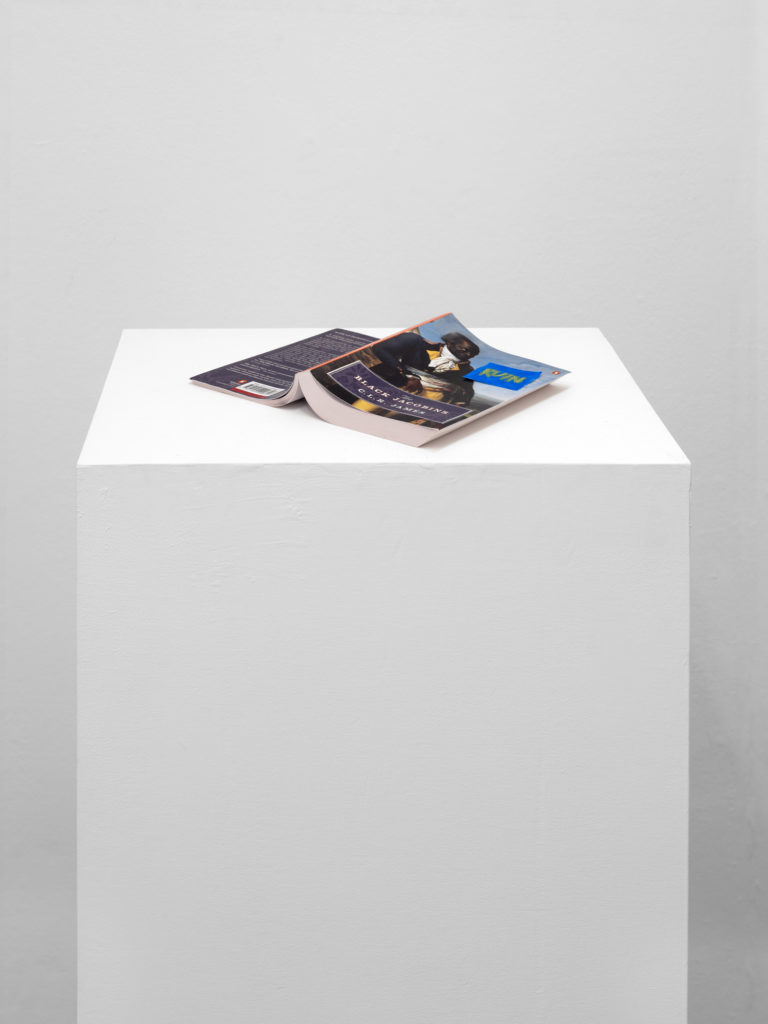

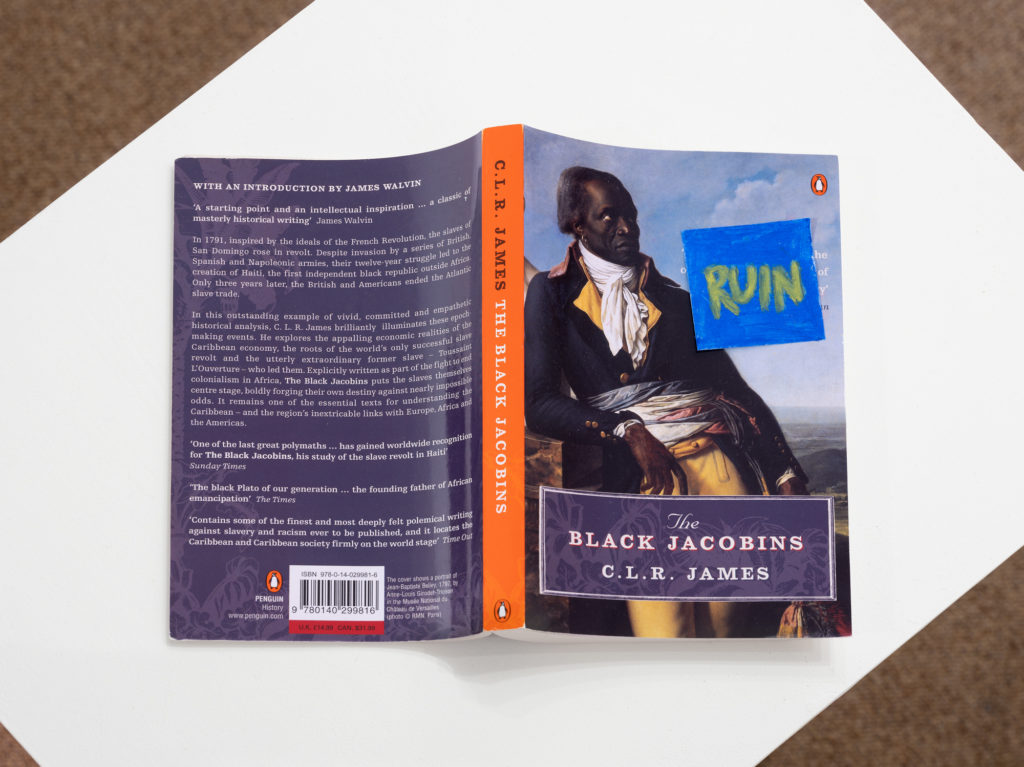

Recent protests around art institutions have experimented in making art accountable to its subject matter, and illustrating how the forms of financial valorization that take place in art echo wider social structures. These protests have inspired various defenses of the inviolability of the artwork and the autonomy of art from the social. The text of the video Ruin I is a fragment taken from a longer reflection by the artist on her experience of one such controversy. A partnering work, Ruin II, is simply a copy of CLR James’s seminal work The Black Jacobins labelled with a post-it. On dramatically different levels (the Haitian Revolution began modernity, whereas recent art controversies have simply marked a minor new era in cultural production), both works gesture to how, when social critique is articulated through blackness, it is received by the liberal mainstream as if threatens total destruction.

- HB, in the third person

Works (from left to right):

The Ruler, 2020

Framed book cover, pen

34.5 x 28 x 3 cm

Ruin I, 2020

HD video

4 minutes, looped

Edition of 3 + II AP

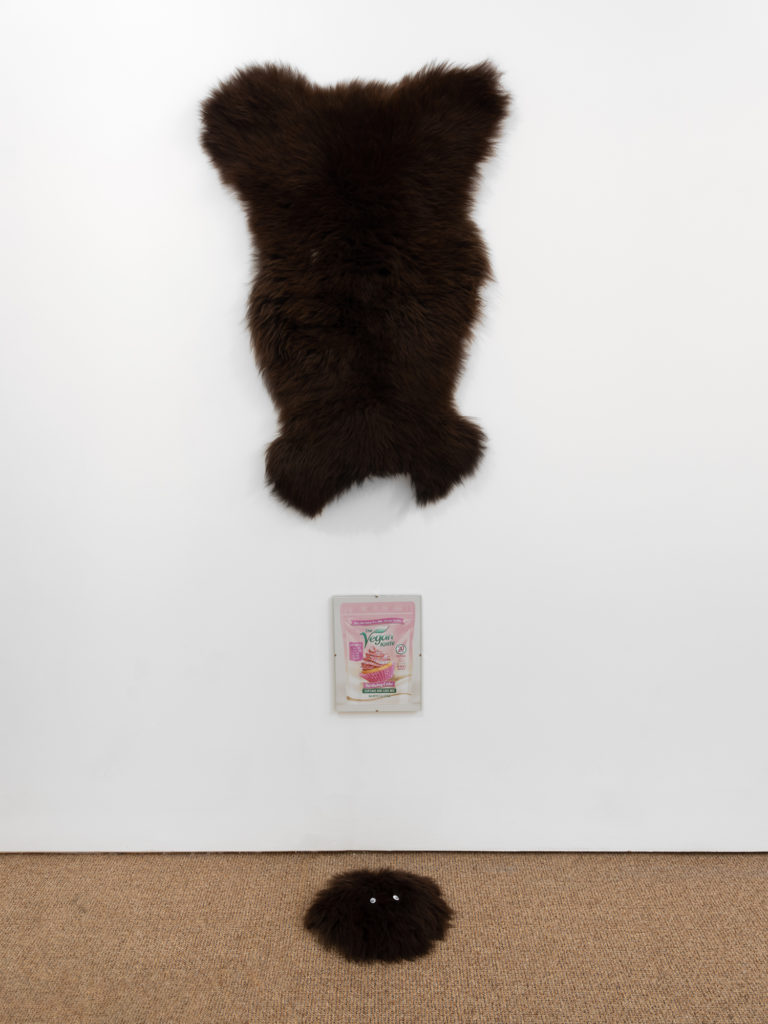

The Hunt II, 2020

Fake sheepskin, framed photograph, googly eyes

Dimensions approximate: 186 x 64 x 37 cm

Oof, 2020

Oil on canvas

180 x 170 cm

Bastille, 2020

Bricks, pages from The 120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade, 1785

Dimensions variable

Ruin II, 2020

Paperback copy of The Black Jacobins by C. L. R. James, 1938, post-it note, pastel, plinth

Plinth: 90 x 45 x 35 cm; Book: 26 x 20 x 2 cm

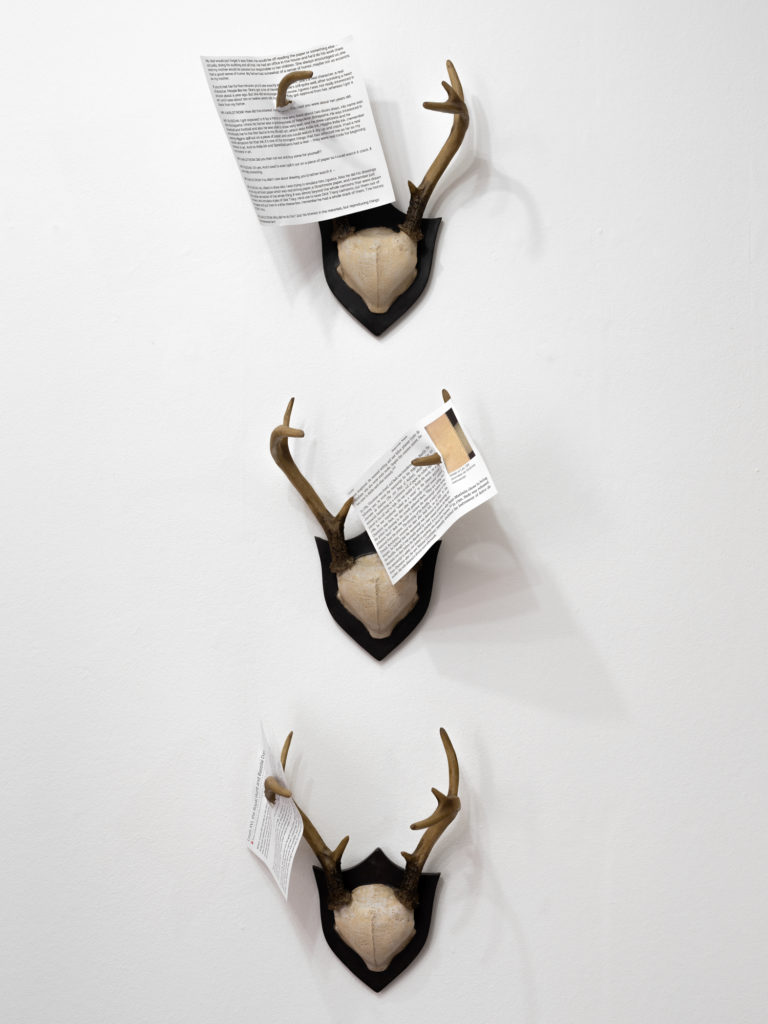

The Hunt I, 2020

Three fake deer antlers, pages from: Oral history interview with Ed Ruscha, 1980 October 29 – 1981 October 2 for

the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; Wikipedia page on Marquis de Sade; blog post on Louis XVI,

the Royal Hunt and Bastille Day

Dimensions approximate: 102 x 25 x 20 cm