Arcadia Missa is pleased to present The person who is recording cannot intervene, a group exhibition curated by Ruth Pilston and featuring works by Alan Michael, Claire van Lubeek, Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings and Kayode Ojo.

“I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking… Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.”

It is with this metaphor that Christopher Isherwood describes his eponymous character within the opening chapter of his semi-autobiographical novel Goodbye To Berlin. An account of the experiences of a fictionalised version of himself in the decline of the Weimar Republic, Goodbye To Berlin documents snapshots of life in 1930s Germany, focusing on those who, like Isherwood, were most threatened by Nazi intimidation: a teenage Jewish heiress; the young gay couple Peter and Otto; the decadent English cabaret singer Sally Bowles (a character later brought to life by Liza Minelli in a straight-washed version of the story, the 1972 musical Cabaret).

As a writer facing the rise of xenophobia and ethnonationalism, it became the role of Isherwood to immortalise, to memorialise the declining society he was immersed in. The person who is recording cannot intervene aims to explore the artist as image maker, as ‘a camera with its shutter open’. The exhibition considers the role of art as documentation, encompassing photorealist painting, sculpture and photography. In a time like the decline of Weimar Germany, is it possible for the artist, or writer, to remain, as Isherwood states, ‘quite passive’? To record and not to think?

In On Photography, Susan Sontag (who, in her seminal essay Notes On ‘Camp’, promoted Isherwood as one of the first novelists to explicitly consider the concept of ‘camp’) lingers on this idea of recording experience through photography . Sontag wrote that ‘while all modern forms of art claim some privileged relation to reality, the claim seems particularly justified in the case of photography.’ To Sontag, the camera produced ‘images of truth’; the written word was instead ‘an interpretation, as are handmade visual statements, like paintings and drawings’. In On Photography, Sontag wrote that ‘the person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.’ The title of this exhibition draws from that idea, aiming to interrogate Sontag’s hierarchy of truth, questioning photography’s ‘privileged relation to reality’, by placing different mediums, or modes of recording, side by side.

Included in The person who is recording cannot intervene are a series of photographs by New York-based artist Kayode Ojo. Held in slick mirrored frames, the photographs are high-gloss, candid images, documenting gallery and museum after-parties, snapshots of a scene in which Ojo is immersed. Photos are at once documentarian, yet, as Sontag would say, ‘haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience’: even though the photographs hold up a mirror to reality, each image, much like his work in painting and sculpture, is instilled with a distinct visual language.

It is these ‘tacit imperatives of taste and conscience’ that haunt all forms of image-making, from painting to videography. Something For The Boys, Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings’ 2018 video filmed across two iconic Blackpool queer venues, endeavours to create a lasting record of a receding queer culture. Following on from their documentarian approach in their 2016 film UK Gay Bar Directory, Something For The Boys is influenced by Quinlan and Hastings’ subjective perspective, Sontag’s ‘conscience’, on the ongoing collapse of queer scenes and safe spaces. Combining staged performances and film of archival photos, the video exemplifies what Sontag refers to as photography’s ‘twin capacities to subjectivise reality and to objectify it’.

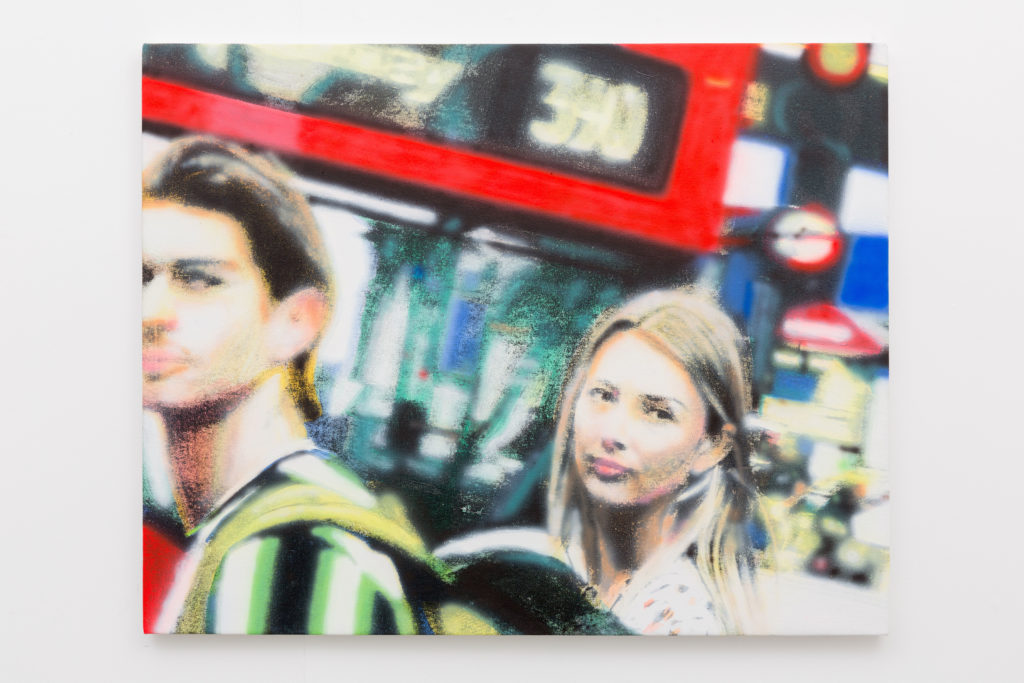

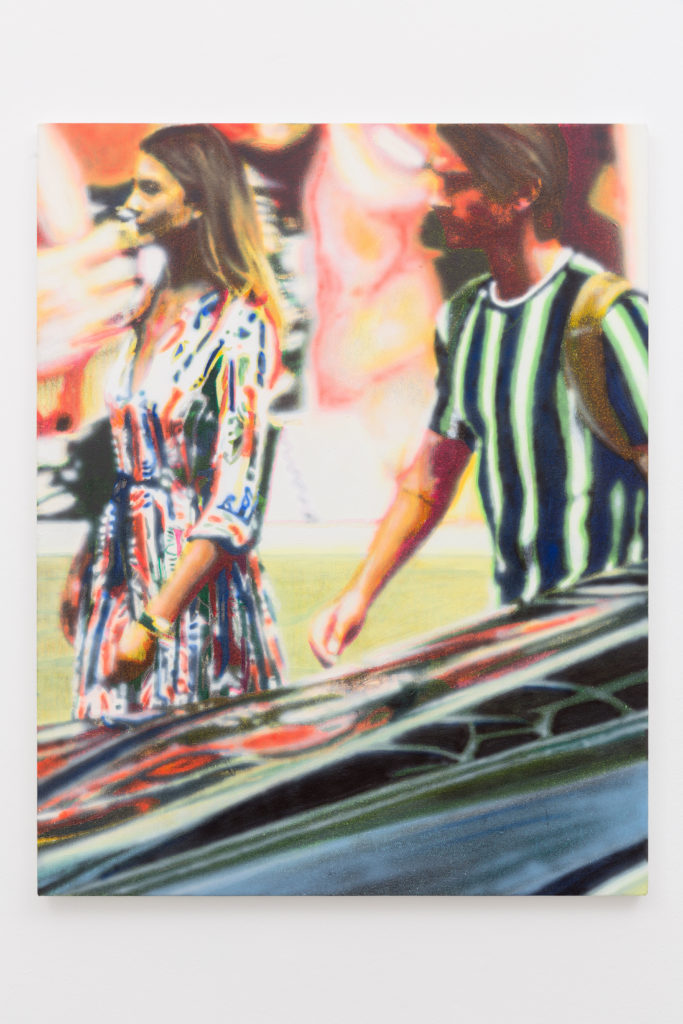

As in Goodbye To Berlin and Something For The Boys, this feeling of documenting a place on the edge of collapse is pertinent to Alan Michael’s paintings. Based on photographs of agency models walking the streets of central London, the series references the familiar tropes of street-photography and fashion editorials, in an attempt to interrogate the politics of image-making, of processing and representing reality in a time of pessimism.

Claire van Lubeek’s Baby Bar, composed of tiny ceramics and modified images and objects, imagines the last open bar in a dystopic, post-apocalyptic world. Creating a bar staffed by society’s most vulnerable, babies, van Lubeek questions the inequalities of a capitalist system and its representations. In On Photography, Sontag writes ‘cameras miniaturise experience, transform history into spectacle’ but here the process is reversed; the miniature experience is blown up, the spectacle of this tiny bar at the end of the world is magnified, showing details that might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

Working from Sontag’s description of photography as ‘an act of non-intervention’, The person who is recording cannot intervene questions the role of the image-maker as the passive recorder of events. As we’ve seen queer spaces shut and, much like in Isherwood’s Berlin, a proliferation of right-wing views across media (including art), can we (or, perhaps more importantly, should we) create an objective image of this reality?

Works

Gallery (from left to right):

Alan Michael,

Untitled, 2019

Silkscreen and acrylic on canvas

68 × 86 cm (26 ¾ × 33 ⅞ inches)

Kayode Ojo

Party to Benefit International Rescue Committee, Madame X, New York, NY, 2018

Archival pigment print

16 x 13 inches (40.64 Å~ 33.02 cm)

16 ½ × 13 ½ inches (41.91 × 34.29 cm) (framed)

Edition 1/3 + II AP

Kayode Ojo

Afterparty for “Juliana Huxtable: A Split During Laughter at the Rally” at Reena Spaulings Fine Art,

Max Fish, New York, NY, 2017

Archival pigment print

16 x 13 inches (40.64 Å~ 33.02 cm)

16 ½ × 13 ½ inches (41.91 × 34.29 cm) (framed)

Edition 1/3 + II AP

Kayode Ojo

Afterparty for “Janiva Ellis: Lick Shot” at 47 Canal, Mika Japanese Cuisine & Bar, New York, 2017

Archival pigment print

16 x 13 inches (40.64 Å~ 33.02 cm)

16 ½ × 13 ½ inches (41.91 × 34.29 cm) (framed)

Edition 1/3 + II AP

Claire van Lubeek

24/7 9, 2017

Laserjet print, framed

100 x 70 cm (39 3/8 x 27 1/2 inches)

Edition 1/3 + II AP

Claire van Lubeek

The Baby Bar, 2017

Cardboard, fimo clay, paper, paint, hair

95 x 35 x 20 cm (37 3/8 x 13 3/4 x 7 7/8 inches)

Alan Michael,

Untitled, 2019

Silkscreen and acrylic on canvas

86 × 68 cm (26 ¾ × 33 ⅞ inches)

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings

Something for the Boys, 2018

HD video with sound

16 minutes 34 seconds

Edition 2/5 + II AP

Office (from left to right):

Alan Michael

Today Is, 2017

Oil on canvas

145 x 102 cm (57 1/8 x 40 1/8 inches)

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings

Fuck Me On The Middle Walk 12, 2017

Pencil on paper, framed

21 x 29.7 cm (8 1/4 Å~ 11 3/4 inches)

40 x 50 cm (15 3/4 Å~ 19 5/8 inches) (framed)